Brazil’s Historic Racing Battleground

Table of Contents

Introduction: Why Interlagos Still Matters in Global Motorsport

Origins and Evolution of the Autódromo José Carlos Pace

Track Layout and Engineering Profile

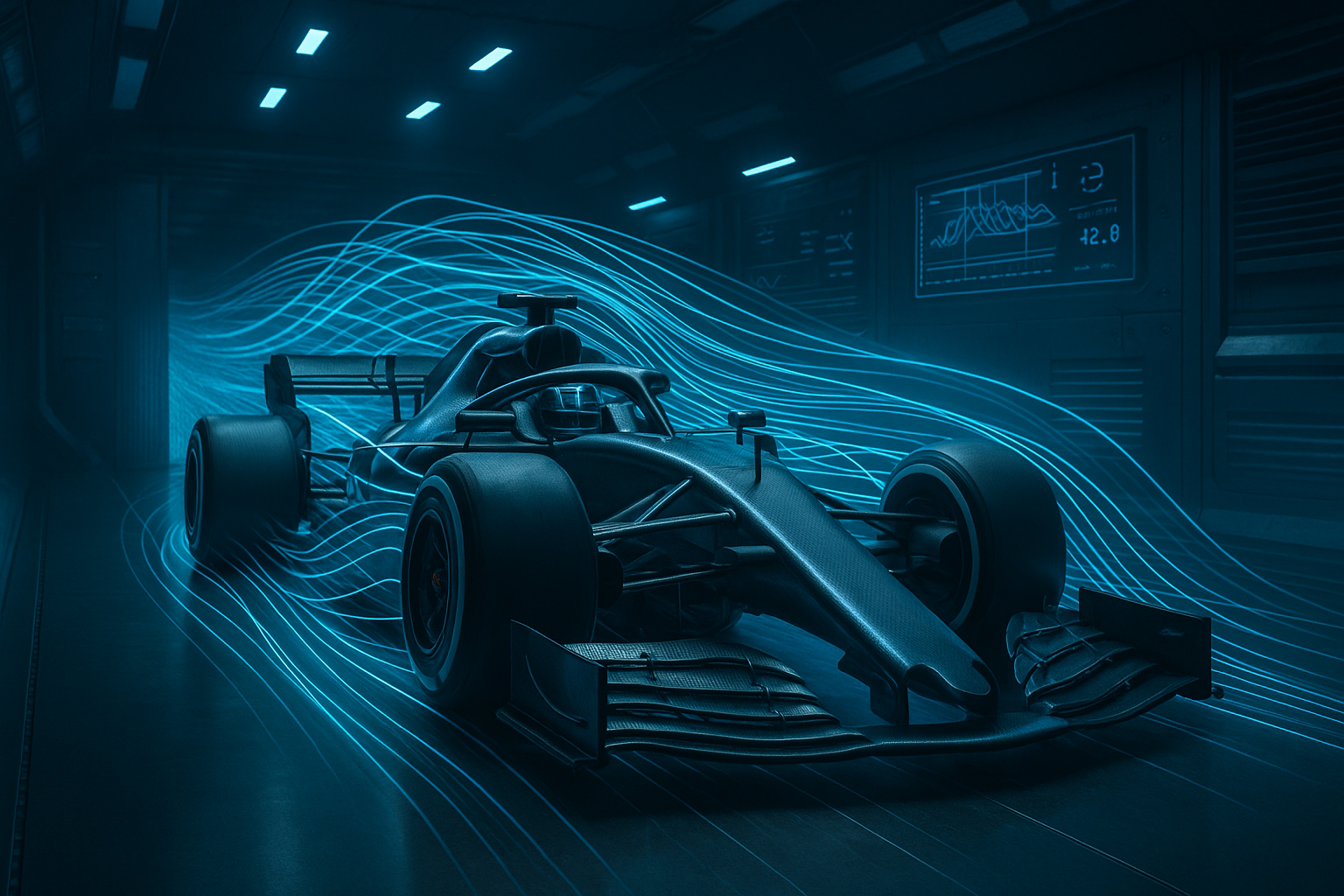

Aerodynamic and Mechanical Demands

The Weather Factor: São Paulo’s Microclimate in Action

Legendary Moments at Interlagos

Cultural Importance and National Identity

Strategic Variables in Race Weekend

Conclusion: The Enduring Relevance of Interlagos

Introduction: Why Interlagos Still Matters in Global Motorsport

In a world increasingly dominated by hermetically sealed racing facilities and laser-leveled asphalt, Interlagos remains an anomaly — a circuit that resists sterilization, refuses to be tamed, and continues to command reverence from engineers, strategists, and drivers alike. Officially known as the Autódromo José Carlos Pace, this historic track in the southern reaches of São Paulo is not simply a venue on the Formula 1 calendar. It is a living artifact of motorsport’s most essential tensions: between man and machine, chaos and control, legacy and evolution.

Since its inauguration in 1940, Interlagos has occupied a rare stratum within global motorsport. It is a circuit born not from computer modeling or FIA simulation protocol, but from the natural contours of the land — a racetrack defined by elevation, unpredictability, and human ingenuity. In this respect, it belongs to the same lineage as Spa-Francorchamps and Suzuka: tracks where the asphalt was draped over terrain, rather than carved through it.

Yet its relevance extends far beyond nostalgia. Interlagos challenges modern F1 machinery in ways few circuits still can. Its counterclockwise configuration imposes asymmetric loads on the driver’s body, requiring dedicated physiological preparation. Its compressed lap length — just over 4.3 kilometers — generates a relentless rhythm of attack and reset, forcing teams to make strategic decisions with little margin for correction. And above all, its microclimatic volatility — shaped by altitude, urban density, and seasonal instability — introduces a layer of atmospheric unpredictability that no wind tunnel or simulator can replicate.

The track’s legacy is deeply interwoven with the narrative of Formula 1 itself. From the defiant brilliance of Ayrton Senna’s 1991 victory on a failing gearbox, to the operatic drama of Hamilton and Massa in 2008, Interlagos has functioned as both a crucible and a stage — producing results that were neither predictable nor engineered, but earned in real time, under pressure, and in front of a nation.

This post will dissect Interlagos not as a nostalgic monument, but as an active, evolving entity. We will examine its topographical complexity, its engineering implications, its strategic volatility, and its cultural gravity — all of which contribute to its unique and enduring status within the highest tiers of motorsport.

Interlagos matters not because it is old, or dramatic, or emotionally resonant — though it is all of those things. It matters because it still pushes racing to its physical, technical, and human limits. And in a sport increasingly defined by precision, predictability, and pre-race data certainty, Interlagos remains gloriously, stubbornly, alive.

Origins and Evolution of the Autódromo José Carlos Pace

The Birth of Brazilian Motorsport

Interlagos emerged not just as a racetrack, but as a declaration of intent. In the late 1930s, Brazil was undergoing industrial transformation, driven by a surge in infrastructure investment, nationalist sentiment, and a rising upper-middle class fascinated by European automotive culture. São Paulo, already the epicenter of Brazil’s economic expansion, became the natural home for the nation’s first purpose-built circuit.

Construction began in 1938, and by 1940, the original Interlagos layout stretched 7.96 kilometers, carved into the undulating plateau between the Guarapiranga and Billings reservoirs — hence the name “Interlagos” (between the lakes). Unlike the banked, oval-inspired tracks of North America or the flat airfields of post-war Europe, Interlagos was a true road course: raw, fast, narrow, and intensely physical.

Its early corners — names like Curva do Sol, Ferradura, and Retão — were forged not by engineering simulations, but by topographical necessity. The layout flowed naturally with the terrain, creating unpredictable camber transitions, blind entries, and elevation shifts that made it brutally unforgiving. At a time when safety infrastructure was rudimentary at best, the challenge of Interlagos was not only mechanical — it was mortal.

Brazilian motorsport soon found its spiritual and practical center at the track. It hosted major national and international events long before Formula 1 arrived in 1972. For local drivers like Emerson Fittipaldi and José Carlos Pace, it was more than a home circuit; it was a proving ground and a spotlight, where domestic talent could challenge European excellence on equal footing.

The circuit was renamed in 1985 in honor of José Carlos Pace, a São Paulo-born F1 driver who claimed his sole Grand Prix victory at Interlagos in 1975 and tragically died in a plane crash two years later. By then, the legend of the track was well established — but its place in the modern era would soon come into question.

Interlagos Before and After the 1990 Redesign

By the 1980s, the original Interlagos had become untenable for contemporary Formula 1. The lap was too long for effective TV coverage, the facilities were dated, and the safety standards fell well short of FIA expectations. With the rise of turbocharged engines and increasing cornering speeds, the narrow asphalt and nonexistent runoffs posed a critical risk.

In 1990, after a ten-year absence from the F1 calendar (during which Rio de Janeiro’s Jacarepaguá circuit hosted the Brazilian Grand Prix), Interlagos returned in a radically revised form. The track was shortened to 4.325 km, reshaped to emphasize safety while preserving the original character. Crucially, it retained iconic sequences like the Senna S, Curva do Sol, and the high-speed Subida dos Boxes, preserving the link to its past while opening it to a new generation of competition.

The redesign — a collaborative effort involving local engineers and FIA consultants — was not simply a truncation. It was a surgical transformation, recalibrating the rhythm of the circuit. What was once a sweeping, high-speed road course became a technical short lap with relentless transitions, demanding constant modulation of throttle, brake, and steering. It was now a circuit of momentum and flow, where lap time is won not by top speed, but by execution and precision.

Critically, the circuit’s elevation profile was preserved, retaining the approximately 43-meter vertical differential from the pit exit up to the braking zone of Turn 1. This topographical integrity ensured that Interlagos remained a test of chassis balance, power delivery, and driver focus — especially under race fuel loads or changing weather conditions.

The modern Interlagos became not only safer but more relevant. Its compressed format made it television-friendly, its layout rewarded skill over engine power, and its high-frequency cornering made it an ideal stress test for evolving vehicle dynamics. It also kept its unique voice: a counterclockwise configuration with real heritage, national significance, and racing unpredictability.

Today, Interlagos stands as one of the few circuits in the world that has successfully transitioned from pre-war motorsport architecture to modern Formula 1 without losing its soul. It is not just a survivor — it is an outlier, a case study in how to modernize with restraint, preserving the essence of racing in the process.

Track Layout and Engineering Profile

Technical Overview of the Modern Circuit

At 4.309 kilometers in length and comprising 15 turns (10 left, 5 right), Interlagos defies modern F1 norms by delivering disproportionate challenge relative to its size. Lap times hover around 1 minute and 10 seconds in qualifying trim, but every second of that lap demands mechanical precision and aerodynamic compromise. What makes Interlagos remarkable is not one feature, but the layering of many: short straights, irregular cambers, aggressive kerbing, and corner transitions that punish imprecision and reward flow.

The lap opens with one of the most critical sequences in all of Formula 1: the Senna S. This chicane, named in honor of Brazil’s most iconic driver, compresses the entry speed of ~310 km/h on the pit straight into a sharp left-right descent. It’s a true setup benchmark — front-end responsiveness and rear stability are simultaneously under scrutiny. Misjudge either, and the corner exit sets a compromised trajectory all the way through Curva do Sol and onto the Reta Oposta, the back straight where most overtaking occurs.

Following the Reta Oposta, the lap transitions into a series of mid-speed corners that dominate Sector 2 — Descida do Lago, Ferradura, Pinheirinho, and Bico de Pato — each demanding careful throttle modulation and maximum rear grip under lateral load. Sector 2 defines Interlagos from an engineering standpoint: its geometry exposes any instability under trail braking, abrupt changes in camber, or deficiencies in traction mapping.

From Junção onward, the circuit climbs again — slowly at first, then steeply through the Subida dos Boxes and onto the main straight, completing a lap that contains no true “rest” zone. The high corner frequency and unrelenting terrain force both driver and car to remain dynamically active throughout.

Elevation, Corner Types, and Setup Challenges

Interlagos features a vertical differential of approximately 43 meters between its lowest and highest points. This elevation change is not cosmetic — it fundamentally alters car balance throughout the lap. Gravity becomes an active participant in vehicle dynamics: downhill braking zones like Descida do Lago amplify forward pitch and brake locking tendencies, while uphill exits such as Junção penalize low-rpm torque delivery and traction control tuning.

In setup terms, this means Interlagos requires high longitudinal stability — especially under mixed grip — and a predictable lateral platform. Teams often run higher ride heights to deal with the undulations and kerbing, particularly in the mid-sector. However, this compromises rear aero stability under load, particularly in Turns 10 through 12, where rapid direction changes stress diffusers and plank contact zones.

Compounding the challenge is the necessity for aero balance adaptability across sectors. Sector 1 and 3 demand low drag and strong straight-line performance, while Sector 2 punishes any loss in mechanical grip. This leads to divergent approaches among teams: some favor stiffer rear suspensions and softer fronts to improve rotation; others opt for neutral rake setups that minimize vertical oscillation at the cost of outright turn-in sharpness.

Braking zones at Interlagos are relatively short, but all are loaded with lateral input, making brake migration strategies and pedal modulation critical. Asymmetric tire wear is also a known issue, exacerbated by the anti-clockwise layout, which results in higher thermal load on the left-front and left-rear tires — a notable setup constraint when designing camber and pressure profiles.

The Impact of the Counterclockwise Configuration

While most modern F1 circuits are designed clockwise, Interlagos runs against the grain — literally and figuratively. The counterclockwise layout is more than a novelty. It imposes genuine physiological and mechanical asymmetries that must be addressed in both car setup and driver preparation.

Physiologically, drivers experience increased stress on the right side of the neck and core, particularly in Turns 3, 5, and 10, which produce extended left-hand lateral G-force. Teams often integrate counter-rotational strength conditioning into driver programs specifically for this event. Over a full race stint, even seasoned professionals report disproportionate muscular fatigue compared to other circuits.

From a mechanical standpoint, the asymmetry translates into setup choices that account for uneven load distribution across suspension components. The right-hand side of the car endures more consistent compression, leading teams to modify damper and spring rates asymmetrically, often with subtle preload adjustments to stabilize the chassis under left-corner load peaks. The tire pressure delta between left and right sides can be significant — a rare but necessary condition to maintain thermal balance across the tread surface.

More subtly, steering racks often require custom calibration. The Senna S, Ferradura, and Bico de Pato all demand tight steering radii and quick rack response, particularly on turn-in. Some teams have experimented with progressive rack geometries that provide variable steering sensitivity across the lock range — a concept rarely required on more conventional circuits.

The counterclockwise nature of Interlagos is not an inconvenience. It is a design truth — one that affects everything from driver fatigue to damper curve theory. And it is one more reason why Interlagos remains not just a track with personality, but one with consequence.

Aerodynamic and Mechanical Demands

Downforce vs. Drag Tradeoffs

Interlagos is a case study in aerodynamic compromise. With two long straights (main straight and Reta Oposta) sandwiching a highly technical mid-sector, teams face constant tension between trimming wing angles for straight-line speed and maintaining enough downforce for lateral grip through Sector 2.

While high-downforce packages are often the baseline (especially under threat of rain), some teams opt for medium-downforce trims with enhanced rear stability via suspension geometry — trading some mid-corner performance for overtaking potential and energy efficiency on straights.

| Sector | Aero Priority | Typical Setup Approach | Speed Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sector 1 | Low Drag / High DRS Use | Trimmed rear wing, neutral rake | High (~300+ km/h) |

| Sector 2 | High Downforce Needed | Soft front suspension, high rake | Medium (~150–200 km/h) |

| Sector 3 | Balanced Exit + Top End | Moderate drag, stable platform | Very High (~310+ km/h) |

The DRS zone on the Reta Oposta is relatively short, making clean exits out of Turn 3 (Curva do Sol) critical. Teams with inherently efficient aero packages — like Red Bull in recent seasons — have had a strategic edge here by deploying medium-downforce solutions without compromising cornering grip.

Suspension Setup and Grip Considerations

Chassis setup at Interlagos is heavily dictated by mechanical compliance and terrain reactivity. The circuit’s surface, though resurfaced multiple times, still contains enough elevation shifts, cambers, and curbing to require specific suspension strategies.

| Suspension Parameter | Preferred Setup at Interlagos | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Ride Height (F/R) | Medium / High rear | To absorb elevation changes and maintain diffuser stability |

| Front Suspension Stiffness | Softer than average | Enhances compliance over kerbs in Sector 2 |

| Rear Suspension Stiffness | Medium to firm | Required for stability on power exits (Junção, Turn 3) |

| Anti-Roll Bars | Asymmetric tuning (softer right side) | Counteracts lateral imbalance from counterclockwise layout |

| Damper Response | Progressive compression (esp. rear dampers) | Balances bump absorption with aero platform preservation |

Additionally, Interlagos often rewards teams that prioritize yaw control and minimal lateral delay in direction changes. Corners like Bico de Pato and Ferradura are rhythm-critical and prone to understeer in mid-exit. Hence, limited-slip differential tuning and soft rebound damping are common tools in setup refinement.

Tire Selection Strategy and Degradation Patterns

Interlagos typically generates low to medium tire degradation, depending heavily on ambient conditions. Its abrasive but non-destructive surface, coupled with short stints of full-throttle load, creates a window where tire warm-up is easy, but peak grip is fragile under high lateral stress — especially on the left side.

Pirelli usually brings the softest compounds in the C2–C4 range, anticipating variable weather and high track evolution. However, thermal asymmetry is a constant challenge.

| Tire Axis | Primary Load Zones | Common Issues | Management Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left-Front | Curva do Sol, Ferradura, Turn 12 | Graining under cool conditions | Maintain balanced front toe-out and camber |

| Left-Rear | Senna S, Junção, Descida do Lago | Thermal wear, traction loss | Staggered pressure & gradual throttle mapping |

| Right Tires | General stability/load support | Lower average temps, slow warm-up | Asymmetric camber & stiffer carcass loading |

A significant part of tire strategy at Interlagos also hinges on track temperature, which can swing by over 20°C in the span of a session, due to São Paulo’s microclimate. In cooler races (e.g., 2016), warm-up was a greater threat than degradation. In hotter, dry races (like 2012), rear thermal runaway was more critical.

Teams generally lean toward one-stop strategies under normal conditions, starting on softs (C4) and switching to hards (C2). However, the high probability of Safety Cars (SC) often forces real-time pivots — making real-time telemetry response and pit wall coordination crucial.

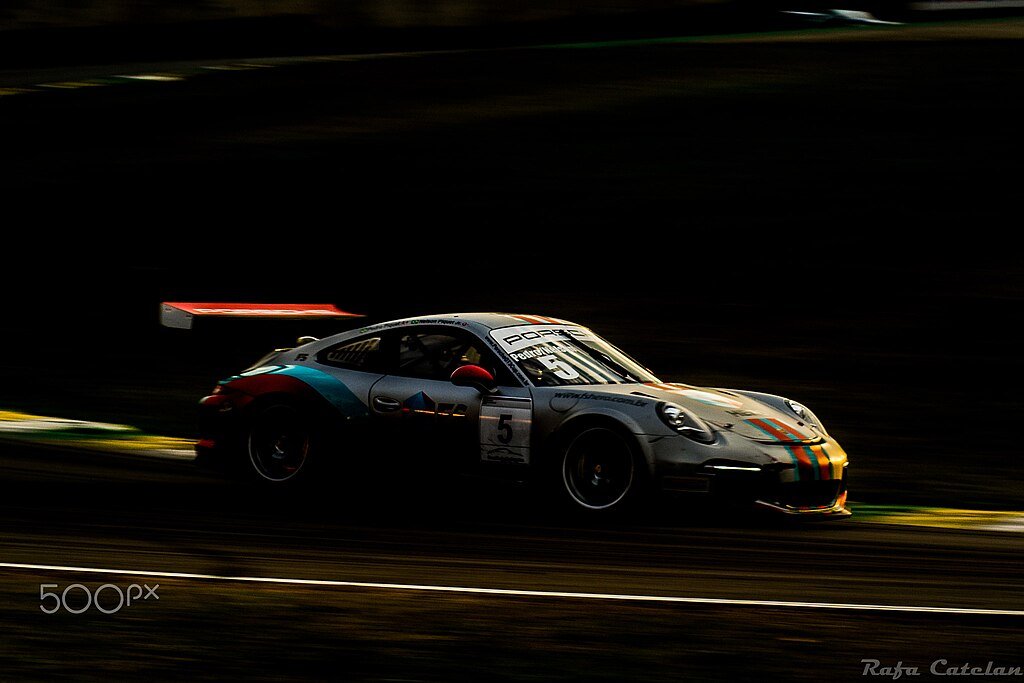

The Weather Factor: São Paulo’s Microclimate in Action

Few variables unsettle a race weekend at Interlagos more than its weather — not because of its extremity, but because of its unpredictability. Situated at approximately 800 meters above sea level and bordered by urban sprawl, Interlagos exists within a climactic tension point where tropical humidity, rapid cloud formation, and shifting wind patterns collide. The result is a microclimate that can change not only day to day, but sector to sector within the same lap.

While Formula 1 teams now rely on high-resolution radar and localized atmospheric modeling to forecast weather changes with impressive accuracy, Interlagos continues to defy expectation. Due to its basin-like topography and dense surrounding infrastructure, cloud formation over the circuit often follows hyper-localized patterns that escape broader meteorological prediction. A session can begin under filtered sunlight and degrade into patchy rain within minutes — or, more dangerously, fall victim to a drying track that rewards or punishes tire decisions within a single lap window.

This phenomenon is not theoretical — it is foundational to Interlagos’s racecraft identity. Engineers must prepare for thermal variance not just across days, but within stints. The ambient temperature may remain steady, but sudden humidity spikes or reduced solar exposure due to cloud cover can radically shift tire surface behavior, brake cooling efficiency, and aero balance. The difficulty is compounded by the track’s short lap length: the time gap between changing conditions on one part of the circuit and their arrival at another is often less than sixty seconds, leaving almost no time for driver feedback to inform pit strategy.

The 2003 Brazilian Grand Prix remains the canonical example of Interlagos weather chaos. What began as a wet race quickly turned treacherous, with standing water and aquaplaning zones emerging at different parts of the circuit. The tire suppliers were split on optimal compounds, teams were caught on crossovers between intermediates and full wets, and the result was a race that featured multiple crashes, red flags, and an eventual victory decided only after the podium — when Giancarlo Fisichella was awarded the win due to a red flag countback procedure.

More recently, in 2016, Lewis Hamilton delivered one of the finest wet-weather drives of the modern era, leading every lap of a race marred by poor visibility, repeated incidents, and extreme aquaplaning through Descida do Lago. The track refused to dry uniformly, with sectors 2 and 3 remaining saturated while the pit straight began to develop a drying line — rendering tire selection a gamble and downforce levels an ongoing compromise. The race demanded not only precision from the driver but a kind of psychological resilience not typically seen in dry-weather Grand Prix.

These events are not outliers — they are symptomatic of a venue that refuses to follow the procedural logic of newer facilities. For engineers, this means designing race simulations with scenario trees that account for extremely narrow decision windows. For drivers, it means finding grip where none should exist. And for fans, it means Interlagos rarely delivers a race that goes to script.

Ultimately, the weather at Interlagos is not a backdrop. It is a protagonist — a destabilizing force that turns preparation into adaptation and ensures that, no matter how evolved Formula 1 becomes, the elements can still rewrite the ending.

Legendary Moments at Interlagos

There are racetracks where championships are won, and then there are those where racing’s mythology is written. Interlagos belongs firmly in the latter category — not simply because titles have been decided there, but because of the how and why behind them. Its asphalt is not merely raced upon; it absorbs and reflects the triumphs and heartbreaks of drivers whose names are now etched in motorsport folklore.

Senna, 1991: The Victory That Transcended the Machine

When Ayrton Senna crossed the finish line at Interlagos in 1991, arms frozen in agony and voice cracking through the team radio, it was more than a race win. It was a national catharsis.

Senna had never won at home. Despite three world titles and countless moments of genius, Interlagos — his home soil, his emotional epicenter — had eluded him. That Sunday, he started from pole and built a commanding lead, but midway through the race, his gearbox began to fail. First, fourth gear was lost. Then third. Then fifth. By the end, he was nursing the McLaren MP4/6 around the circuit with only sixth gear functioning — a mechanical straitjacket around the throat of the most precise driver of his era.

With every lap, the physical toll became visible. His head slumped to one side; his arms barely obeyed. But the circuit, that counterclockwise serpent he knew better than most, became both his adversary and his instrument. He coaxed the car across the line, winning by just under three seconds.

After the checkered flag, Senna could barely lift the trophy. The crowd — tens of thousands strong — did it for him. It wasn’t just a Brazilian winning at Interlagos. It was Ayrton winning in pain, against physics, on a day when willpower triumphed over technology. A moment not remembered as a victory, but as a legend.

Hamilton vs. Massa, 2008: The Final Corner of Fate

Interlagos is no stranger to championship drama, but nothing before or since has matched the operatic intensity of 2008 — a race that delivered two parallel storylines and one of the most heart-wrenching climaxes in F1 history.

Felipe Massa, son of São Paulo, drove the race of his life. From pole position, he controlled the Grand Prix with poise and speed, navigating intermittent rain showers and late pit strategy with the calm of a veteran. He crossed the finish line victorious, greeted by a stadium’s worth of euphoria. In the Massa family garage, champagne flowed. Mechanics cried. Brazil had its champion.

But then, on the final lap, the track conditions betrayed a twist of fate. A brief shower had scrambled tire choices. While Massa’s Ferrari team reacted perfectly, Lewis Hamilton and McLaren opted for a late switch to intermediates. It seemed too late. Hamilton was only sixth — a position that would gift the title to Massa.

Then came the final corner. Timo Glock, on dry tires, was losing grip fast. In the final braking zone before the checkered flag, Hamilton caught and passed him — reclaiming fifth, and with it, the championship.

In the Ferrari garage, silence fell like a curtain. Massa, who had already wept in celebration, stood in stunned disbelief. In just 39 seconds, he went from world champion to runner-up.

That finish didn’t just define a season. It changed the emotional vocabulary of modern F1. Massa became a symbol of dignity in defeat. Hamilton became a legend of the future. And Interlagos — once again — became the stage where the sport’s most human moments were laid bare.

Fisichella in 2003, Schumacher in 2006: The Circuit of Unfinished Stories

Not every Interlagos legend ends in a title — but each tells a truth about the nature of racing.

In 2003, torrential rain turned the circuit into a minefield of standing water and zero visibility. Among the chaos, crashes piled up: Alonso, Webber, Montoya — all caught by the unpredictable surface. Through it all, Giancarlo Fisichella, driving for Jordan, found rhythm in the storm. He crossed the line in second, behind Kimi Räikkönen — or so everyone thought. Hours later, after analyzing timing data frozen at the moment of the red flag, it was determined Fisichella had led one lap earlier. Victory was his. It was Jordan’s final win in Formula 1, and one of the strangest podium reversals in the sport’s history.

Then came Michael Schumacher’s 2006 farewell, at least in its first act. Starting from 10th after engine issues in qualifying, Schumacher suffered a puncture early in the race and dropped to 19th. What followed was a masterclass of overtaking — not through DRS, not with strategic pit windows, but on pure racecraft. One by one, he carved through the field, eventually finishing fourth. It wasn’t a win. It wasn’t even a podium. But it reminded the world why Schumacher had rewritten the record books — and why he would eventually return.

Cultural Importance and National Identity

The Torcida: Brazil’s Loudest, Most Committed Pit Crew

Formula 1 travels to many places. It races through the deserts of Bahrain, under the lights of Singapore, and through the sterile perfection of Abu Dhabi. But nowhere — and we mean nowhere — do fans treat a Grand Prix weekend quite like the Brazilian torcida does at Interlagos.

Let’s be clear: Brazilian fans don’t watch F1. They live it.

At Interlagos, the grandstands aren’t a passive collection of spectators. They’re an organism. They chant, they sing, they wave flags the size of parachutes. And when a Brazilian driver appears on screen — past or present — the decibel level reaches something approximating jet engine status. It’s not unusual for the crowd to cheer during qualifying laps like it’s a World Cup penalty shootout. Subtlety is not part of the equation — and thank goodness for that.

This is the only circuit where a driver can gain a tenth just by being emotionally lifted through the Senna S by crowd noise. Ask any driver who’s won here — the fans are not a background element. They’re a force field. A very loud, very emotional, very patriotic force field.

Even drivers from other nations have spoken about the electricity in the air during Interlagos weekends. Lewis Hamilton once called the fans “so intense it felt like football.” Jenson Button described it as “hostile, but in a charming way.” And when Felipe Massa led the 2008 race, the crowd transformed into a wave of green and yellow thunder, ready to explode — until fate pulled the rug from under them in the final corner. You could feel the heartbreak radiate through the concrete. And yet, they stayed. They clapped. They felt.

That’s the torcida. They don’t just support — they invest emotionally with compound interest.

Interlagos: Not Just a Circuit, a Cultural Stage

To understand Interlagos is to understand how motorsport feels in Brazil. It’s not a hobby, or a weekend filler between football matches (although, yes, they’ll definitely switch the TV back to Palmeiras after the podium). It’s part of the national fabric. This is, after all, the country that produced Fittipaldi, Piquet, Senna, and Massa — each one a chapter in the collective identity of a nation that cheers not just for drivers, but for destiny itself.

Interlagos weekends are treated like national holidays. Local shops sell Senna memorabilia on sidewalks. Old men argue about Rubens Barrichello’s legacy over plastic cups of cerveja. Children wear replica helmets. And if it rains — which it always does — no one leaves. Umbrellas go up, the band keeps playing, and somewhere in the middle of all of it, someone yells, “vai que dá!”

Because for Brazilians, Interlagos isn’t just about F1. It’s a stage for narrative. For hope. For resilience. And sometimes, heartbreak. The asphalt carries not just rubber and oil — but memories, pride, and that irrepressible belief that, somehow, this year will be different.

Strategic Variables in Race Weekend

Pit Lane Risk and Real Estate: Tight Margins, High Impact

Interlagos presents a deceptively simple pit lane profile: relatively short entry and exit durations (typically between 20.5–22.0 seconds stationary loss in Formula categories) and low pit lane speed limits (~60 km/h for most series). However, the pit exit feeds directly into Turn 2, mid-compression in the Senna S sequence. This creates a compounded risk — not just of rejoining into traffic, but of rejoining into a car mid-trajectory on cold tires, with compromised grip and driver visibility.

In multi-class racing (e.g., WEC), this scenario becomes even more volatile. LMP2s exiting the pit may interrupt GTE flow through Sector 1, forcing a delay chain that cascades across multiple classes. In closed-field formats like Stock Car Brasil, where safety car neutralizations are frequent, pit timing becomes less about ideal degradation windows and more about maximizing virtual clean air after safety-neutralized compression.

Strategically, this means pit timing is often driven by what might happen — not what is currently happening.

Undercut and Overcut Mechanics: Clear Air Is the Currency

At Interlagos, the undercut is historically powerful in high-deg conditions (e.g., F1 C4-C5 scenarios) but volatile in others. The lap is short, which minimizes the delta available from new tires, and there are few long corners to build up surface temperature. However, when degradation is front-limited — which is often the case due to the left-front load in Turns 5 and 12 — a well-timed undercut can net 2–3 positions if traffic is avoided.

The overcut becomes viable in cooler conditions or damp-dry transitions, especially when a rival’s out-lap is compromised by traffic on Reta Oposta or a poor warm-up phase. Teams using stable compounds (e.g., medium tires in F1 or slick-hard options in Stock Car) can stretch stints by 2–4 laps and execute a late overcut if in-lap deltas are preserved.

Critically, undercut success depends heavily on whether the driver ahead is in Sector 2 when pitting — the worst-case scenario due to traffic compounding and limited overtaking zones. This creates a secondary strategy axis: timing the pit not just for tire life, but for spatial track modeling.

Safety Car and VSC Probability: High-Stakes Windows

Interlagos carries a statistically high probability of Safety Cars across all major series due to tight runoff areas, limited crane access in Sector 2, and weather volatility. From 2007 to 2023, approximately 70% of F1 races included at least one SC/VSC event. In Brazilian Stock Car, it’s even higher, largely due to wheel-to-wheel congestion and bodywork attrition in the midfield.

In strategic terms, this creates pressure to leave flexibility in pit windows — favoring split-strategy deployments (e.g., car A stops under SC, car B stays out to control restart pace or gain real estate on a split delta).

Teams often simulate 6–8 possible race scenarios around expected safety car windows (usually Lap 5–15, 25–35, and post-Lap 50 in longer races). Decision trees incorporate probabilistic event models: crashes at Turn 1, mechanical failures at Junção, or spinouts on damp kerbs at Turn 10.

If the race is wet or declared damp, intermediate-to-slick crossover points become race-defining. This is less about absolute temperature, and more about line evolution. Due to Interlagos’s narrow width and high rear torque zones, the crossover is late — slicks become viable only once ~65% of the track has a defined dry line. Committing early (à la Hamilton 2016) can yield massive gains, but only if pit delta aligns with clean sector exit.

Overtaking Zones and Qualifying Priority

Despite the passionate rhetoric about Interlagos offering “overtaking opportunities,” true pass completion zones are limited and conditional:

Turn 1 (Senna S) – Primary zone. Requires DRS assistance or significant exit speed delta from Turn 12. In WEC or Stock Car, requires strong top-end and slipstream cooperation.

Turn 4 (Descida do Lago) – Secondary zone. Very effective when traction from Turn 3 is clean and tires are fresh. Risk of outside dive from trailing car makes this corner vulnerable on restarts.

Turn 10 (Bico de Pato) – Rarely used. Only viable in multi-class lapping or when opponent defends wide from Turn 9.

Turn 12 (Junção) into main straight – Setup move, not overtake. Poor exit here ensures vulnerability into Turn 1, but passing into Turn 12 is near-impossible due to short braking zone.

Because of this, qualifying remains disproportionately important. In F1, 5 of the last 8 races were won from the front row. In Stock Car Brasil, grid position matters less due to reverse grid sprints and race 2 strategy. In endurance categories, pole position is more psychological than practical — what matters is minimizing time spent in class-congested sectors.

Final Word from the Pit Wall

Interlagos is a strategic paradox: a short lap with long-term consequences. The compressed nature of the circuit forces every decision — pit timing, compound selection, driver rotation in endurance stints — to be made within reduced margins. There is little room to recover from a miscalculation. But for those who plan with flexibility, model live degradation profiles accurately, and predict the microclimate’s moods, it offers one of the richest decision-making environments in modern motorsport.

This is a circuit where success is rarely built on outright pace. It’s built on understanding the track’s tempo — and knowing when to change your own.

Conclusion: The Enduring Relevance of Interlagos

Interlagos is not the fastest circuit on any calendar. It doesn’t boast the most modern garages, the longest straights, or the flashiest paddock suites. But what it does possess — and what so many other tracks have traded away in the pursuit of refinement — is soul.

Here, every corner tells a story, and every lap contains variables that even the most powerful data models can’t fully capture. It is a circuit that breathes with the weather, reacts to the moment, and punishes misjudgment with a ruthlessness that feels more human than mechanical.

For engineers, Interlagos is a systems test — one that compresses aerodynamic philosophy, tire thermodynamics, driver ergonomics, and strategic modeling into a 70-second lap repeated with no margin for drift. For strategists, it’s a roulette table disguised as a racetrack. For drivers, it is both a playground and a proving ground, where flow and force must be balanced in real time. For fans, it’s theater. Tension. Emotion. Memory.

The track is not timeless because it resists change. It is timeless because it evolves without surrender. From its pre-war roots as a brutal, high-speed challenge through its 1990 rebirth as a technical short-form circuit, Interlagos has stayed relevant by being essential — a venue that refuses to disappear into symmetry and predictability.

Even as the sport turns increasingly toward engineered parity, wind tunnel simulators, and GPS-perfect pit stops, Interlagos remains gloriously imperfect. The curbs still bite. The weather still lies. And the fans still feel — perhaps more than anywhere else in the world.

If racing is ultimately a human pursuit, a battle of instinct, courage, calculation, and belief, then Interlagos is its most fitting arena. Because here, the outcome is never guaranteed. Only the effort is.

And that, in the age of precision, is what makes it immortal.